Poetry emotions

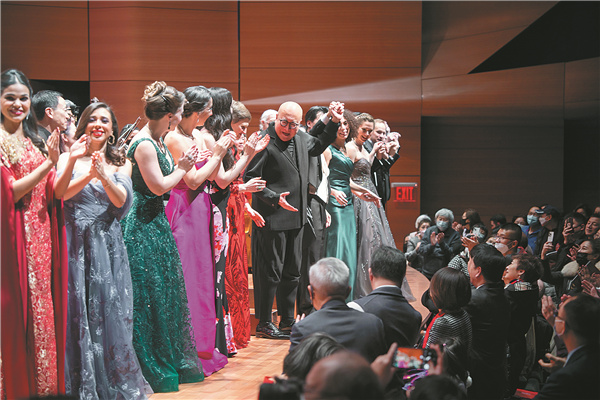

Tian Haojiang (center stage) takes a bow with performers at Lincoln Center's Alice Tully Hall in New York. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Evocative language and inspirational music combine to create a concert that celebrates the emotive beauty of Tang Dynasty verse and the lyrical capabilities of Mandarin, Zhao Xu reports in New York.

"See you not! The Yellow River tumbling from the sky,

Rushing to the ocean by and by!

See you not! Shining mirror mourning white tufts,

Black silk at dawn, snow-white at dusk!"

The lines, passionate and poignant with stirring reflections on the forceful and the fickle, are from Li Bai, an eighth-century Chinese poet whose literary brilliance and inventiveness has often been deemed unsurpassable.

Fueled by unbridled imagination which was in turn watered by the huge amount of wine he apparently imbibed, often in the company of the moon, Li's virile poems have come to epitomize his time — the Tang Dynasty (618-907), an extended period in Chinese history admired for its open society that embraced the rest of the world. (Think about the Sogdian merchants who traveled the ancient Silk Road to the Tang capital, where everything they brought — from spices, gemstones and silverware to their own song and dance — became reasons for celebration.)

Thus, it came as no surprise that this particular poem from Li Bai, tellingly titled Drink to Me, was the piece to open a concert that saw 15 soloists and 15 chorus members from around the world lending their voices — trained in the Western tradition of classical singing — to the ageless lines of 16 ancient Chinese poems, all from the Tang Dynasty. And they did so at Lincoln Center's Alice Tully Hall in New York, against a musical backdrop rolled out by the Philadelphia Orchestra, whose historic 1973 tour of China has made it an emblem of cross-cultural exchange between the two countries.

Bass Wu Wei (left) and baritones, Igor Mostovoi (middle) and Valdis Jansons, sing to the music composed by Nicholas Bentz during the concert. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Yet none of this would have been possible without one man — Tian Haojiang, the internationally renowned opera singer who, 11 years ago, founded the iSING! Suzhou International Young Artists Festival, at which the show premiered in late 2020, before considerable changes were made for the world premiere on Saturday. From the idyllic eastern Chinese city of Suzhou, whose misty waters and manicured gardens have inspired more than a few generations of Chinese writers and artists, to New York, the show has come a long way to connect the dynamism of two cultures across time and space, and to demonstrate, in Tian's words, that "the Mandarin language is for Western concert halls".

"Our original mission was very clear: to promote Mandarin as a lyrical language for opera singers. If niche critical languages like Czech and Russian can make it into the operatic mainstream, Mandarin can be known and sung in the wider world — and even included in the curriculum, the way singers study Czech or Russian diction assiduously," says Katherine Chu, dean of the Tianjin Juilliard School, who's also the head coach and music producer of iSING! Suzhou.

Yet there was a problem. "To sing in Mandarin, you need a repertoire, which we quickly exhausted during the early years of iSING!," says Chu, who saw commissioning new works as the only way forward. The concert, titled Echoes Of Ancient Tang Poems, is the result of a long and meticulous process that started in early 2020 when a group of Chinese literary scholars, critics and translators spent two months whittling 200 Tang poems down to a list of 20, which they deemed as the most suitable to be set to music.

What followed was another selection process, which lasted for five months and involved an international panel of judges. They sifted through more than 100 entries, submitted from 18 countries, by composers who served up their own unique musical renditions of, what seemed on the surface, to be something far removed from the cultural upbringing and immediate experiences of many of the candidates.

Or, maybe not, says Evan Mack, the only composer with two scores featured in Saturday's performance. One is for the poem Up On the Crane Tower, whose author Wang Zhihuan, born more than a decade before Li Bai in 688, philosophized about his own tower-climbing with 10 Chinese characters that translate into "To see a thousand miles in the distance, up another flight one goes."

Yet it was the other 10 characters that come before these that gave Mack the entry point. Searching online for images of the Crane Tower — a replica exists in today's Yongji city, Shanxi province — Mack found a visual equivalent to Wang's lines, "The sun gliding down behind the mountain edge, the Yellow River flows seaward", and a familiar one.

"The landscape jumped out at me as it looks very much like where I currently live in the Adirondack in northern New York — I'm surrounded by mountains and rivers and I wake up every morning to a beautiful sunrise," he says. "For me, it's a familiar picture to paint musically."

From there, the composer went on to let Wang's lesson sink in. "Mountain climbing as a metaphor for life's ascendance is something I ascribe to," says Mack, whose answer to that physical and mental uplift would be a crescendo. "My music is constantly climbing. You'll hear in the background the flowing and fluttering of water, and then you'll hear recurring low-to-high notes throughout that whole piece.

"As the singer was singing the text, the orchestra was always striving for him to sing higher," he adds, noting that his piece also contains a serene aspect innate to the original poem. "A life's journey need not be daunting — instead of racing up a hill, one makes steady, stepwise moves."

Soprano Paula Malagon sings to the music during the concert. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Pure theatricality takes hold in Mack's other work, composed for a poem written by Du Fu, a towering literary figure, who, instead of allowing his sorrows to be washed down by alcohol like Li Bai, chose to nurture them at a time when his beloved country was torn apart by rebelling warlords in the mid-eighth century. This particular poem, in which Du's emotions run the gamut from "grief to relief" to quote Mack, is actually an exception: the author, reveling in the news of the royal army's victory, looked at his wife and children with tears of joy in his eyes as he entertained the thought of returning home to recovered land.

"You really have the feeling how tight this man had been clenching, and how much he had been holding onto in the days and months leading up to that moment. So my idea was to create a little theatrical scene that captures this intense moment, a scene complete with two singers impersonating Du Fu and his wife," says Mack.

The pair's singing overlaid each other, before joining in unison, as they "discussed" the route back home. To treat the original text with what he called "utmost respect", the composer looked at the specific locations of those places mentioned by Du on a map, before overlaying his own "emotional map".

"Think of all the things someone would have to go through if they tied their fate to their country — those are the human emotions I went for," he reflects.

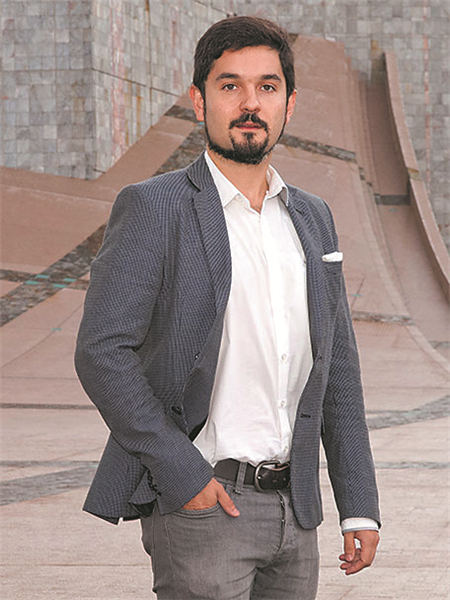

The same patriotism has coursed its way into another Tang poem, by Yang Jiong, a member of the literati who, by a stretch of imagination, envisioned himself forsaking "the life of a sheltered scholar" by "leading a hundred soldiers into war". It required another stretch of imagination for the American composer Nicholas Bentz, who, admittedly, was never one for "bombast", to come up with a score for what he dubbed "a war song".

"The poem's visceral imagery of burning flames, mounted soldiers, howling wind and roaring drums provided me with something that I could latch onto to craft a narrative, and to create an environment for the architecture which is the poem itself," he says. "I let the poem guide my music, written initially for one vocalist, but later adapted for three bass-baritones, to convey the feeling of a gathering of men."

Despite the seeming ferocity, Bentz, who associates his personal style with a "surgical introspectiveness", says that, in the line "Snow has dulled the bright pennants", he did find "a stillness over the battlefield and a moment of reflection" that gives the poem a resonance and draws the composer's heart closer to the man he intended to open a dialogue with.

American composer Nicholas Bentz [Photo provided to China Daily]

To the question, whether he has an analog in mind while composing, Bentz answers with a decisive no. "I wanted to get as close to the source as possible and let the poem stand on its own legs," he says. "So I tried to immerse myself in the aesthetics and used it as a filter through which I could express."

To do that, he has looked beyond the English prose translations and focused on the original text. "You definitely get the images in the English translation, but unless you are really going character by character, you don't understand how those images unfold, how the characters are relating to each other, and which ones can be separated from the line and repeated without muddling or distorting the meaning," he says.

The composer says he believes that all the vocalists were up to their task on Saturday night, with their touching renditions that ranged from passionately ardent, to mightily brooding. One of them is Phoebe Haines, who first went to China in 2016 following a successful audition for iSING! at New York's Juilliard School, where the Londoner was studying privately with a teacher.

"To prepare us, both Mr Tian and Katherine have spoken a lot about each individual poet, their life and how they contributed to the art form. We also did a lot of work around the set formats of Tang poetry, whereby a piece typically contains four or eight lines, each made up of five or seven characters," she says. "They really went into granular detail.

Mezzo Phoebe Haines thanking the audience. [Photo provided to China Daily]

"I believe there's a huge space between just being able to imitate the sound of something and then, on the other very far side of the spectrum, being able to speak the language fluently," she continues. "Between those two goal posts, there's a huge range of understanding that enables one to have a language without becoming a fluent speaker. For all of my colleagues onstage, when they sang in Chinese, they knew not just the pronunciation, but also the meaning of every single syllable, which allowed them to soak in the mood and the weight carried by each Chinese character."

With that being said, the mezzo herself, who also sings in Russian, German and Italian, has decided to take her engagement with the Chinese language one big step further. Since September 2019, she has been taking online Chinese courses with Beijing's renowned Tsinghua University, five days a week, four hours a day.

American composer Evan Mack

"It has given me a huge amount of purpose throughout the pandemic period," she says. It's a feeling shared on various degrees by her fellow artists of the show, among whom was the Spanish composer Fernando Buide, whose score was set for a poem dedicated to a parting friend, titled Send-Off.

"The poem, which not only celebrates friendship, but also evokes the farewell of those closest to our souls, resonated with me profoundly," says Buide, who wrote the music "right in the middle of the most severe lockdown in Spain".

"The precision and depth of the Chinese language is astounding. Being able to write melodies for this wonderful text connects with a universal need to convey our deepest inner emotions through the use of voice … when I composed, the sounds of my childhood ended up appearing under the surface of the music in subtle and unconscious ways," says Buide, who calls his music "reflective and hopeful".

And hope was palpable in the air, as the composers, vocalists and orchestra members met in New York during the rehearsals and onstage, many for the first time since the outbreak of the pandemic.

"Remember I wrote this orchestral piece at a time when we could barely get six people into a room," says Bentz.

Now that travel to China has been gradually reopened, Mack is considering "taking one slice of something and going in-depth", which, in this case, could mean tracing the footsteps of Du Fu through mountains and rivers that might remind him of home in northern New York.

What would Li Bai have said if he were in the audience last Saturday?

"He would have stood up, raised a glass of wine to the moon and told everyone to sing along," says Haines.

Spanish composer Fernando Buide. [Photo provided to China Daily]