A Gripping Mystery

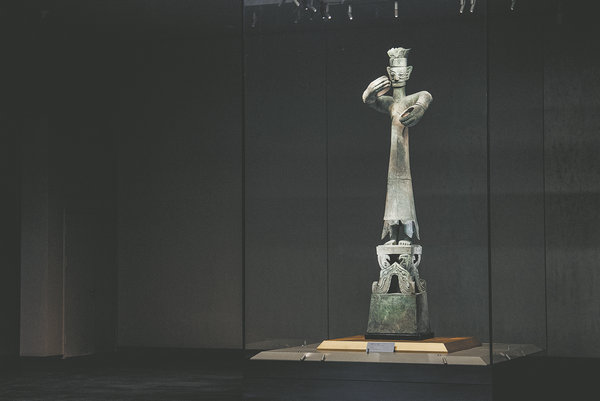

The grand bronze standing man represents one of Sanxingdui's biggest myths. [Photo/THE SANXINGDUI MUSEUM AND THE SHANGHAI MUSEUM]

What was the man holding? This is an inevitable question for anyone who has ever looked up to the famous bronze standing man, unearthed from a pit in Sanxingdui, an archaeological site located in Guanghan city, southwestern China's Sichuan province. During its heyday between 1600 and 1100 BC, Sanxingdui was capital to the ancient kingdom of Shu- Shu being a modern byword for Sichuan- which built around itself a prosperous Bronze Age civilization that dominated the Upper Yangtze River region.

One of Sanxingdui's most identifiable images, the statue, standing 2.6 meters tall, pedestal included, is also one of its biggest puzzles. Researchers have long suggested that the man's stature demonstrates his elevated status, probably as a king or chief priest, or both. Others believe that it may have once been placed on an altar and worshipped by the awestruck people of Sanxingdui.

People argue over just about every aspect of him, from his identity and dragon-patterned clothing, to his majestic headpiece and the pedestal, adorned with images of mythical beasts, upon which he proudly stands. Yet nothing has aroused more interest than his gestures. With arms raised in midair and fingers of both hands circled to form a hole in the middle, the man had almost certainly been holding something, something that is likely to have been lost, or has disintegrated over the course of millennia.

But what was it?

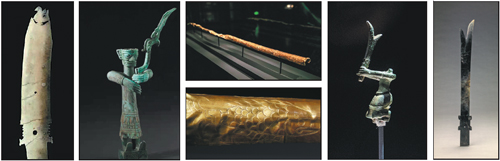

A close-up of his gripping hand. [Photo/THE SANXINGDUI MUSEUM AND THE SHANGHAI MUSEUM]

The gold scepter

"A gold scepter — this is one of the earliest suggested answers," says Hu Jialin, who's behind a well-researched ongoing exhibition at the newly opened Shanghai Museum East, which takes a deeper look at the myths surrounding the ancient civilization of Sanxingdui.

The reason is simple: barely a month before the discovery of the bronze man in August 1986, a 1.42-meter-long gold scepter was unearthed from the site. Weighing about half a kilogram, the scepter was made up of a layer of gold foil wrapped around a wooden stick. With its wooden core long rotted away, the gold scepter, so rumpled that it was initially thought to be a belt, has proved to be one of the biggest of its kind found in China, as well as the rest of the world.

Together with other gold items, including a giant gold foil mask weighing more than 280 grams that was excavated from the site in 2020, the scepter has fueled speculation that the Sanxingdui culture — and the ancient kingdom behind it — had shared direct ties with the far-flung lands to its west, including ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, where gold was the material of choice for the ruling class, and scepters were a recognized symbol of power.

"But there's one fundamental problem: If the tradition of gold making and usage had indeed traveled for thousands of kilometers from the Near East to the Chengdu Plain, where the Sanxingdui culture had prospered, it couldn't have done it alone. In other words, there must have been something else, major crops or even written languages for example, that had made the same journey, of which we haven't yet found any evidence," says Hu, referring to the absence in Sanxingdui of archaeological wheat remains, wheat being cultivated in the Near East at the time.

"In sharp contrast, we have discovered the archaeological remains of millet and rice, grown at the time in the Yellow River basin and the Yangtze River Delta region, respectively."

In the 1980s, Chinese archaeologist Tong Enzheng (1935-1997) came up with his model of a crescent-shaped exchange belt extending from China's northeast to its southwest, arching midway toward the Mongolian steppes and the eastern rim of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Along this belt, the decrease of latitude is compensated by the increase of altitude, resulting in a roughly similar annual average temperature, precipitation and vegetation for this long stretch of land.

China's Arc — that is the term used by world-renowned British art historian and Sinologist Jessica Rawson to describe the region, on the lower southwestern section of which Sanxingdui is located.

"Sharing more similarities than differences, the various nomadic cultures dispersed along this extended belt tended to have more exchanges with one another than with the agrarian societies located to their east," says Hu.

"In my view, the gold tradition of Sanxingdui probably had something to do with the steppe cultures in East Asia, which prized gold and had long worked with the material," he says, conveniently pointing out that, although metal casting appeared in the West approximately 1,000 years earlier than it did in China, it was very unlikely to have influenced the bronze-making of Sanxingdui.

"While arsenical bronze — copper with a large percentage of arsenic — was widely used in the West, the Sanxingdui relics were made using leaded tin bronze, which has a lower melting point and therefore higher fluidity, allowing for the casting of intricate details, exemplified by the bronze items created during China's Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC)."

From left: A fish-shaped jade zhang, with a bird perched at its tip; a bronze figure holding a bird; the gold scepter and its fish pattern; a bronze figure with a missing head holding a forked zhang; and a forked zhang carved out of jade, all from the archaeological site of Sanxingdui. [Photo/THE SANXINGDUI MUSEUM AND THE SHANGHAI MUSEUM]

The elephant tusks

Although the nature of the elephant tusks, unearthed in large numbers from several pits on the site, is still open to debate, their cultural and religious significance is undeniable, making them a possible answer to the question.

"During the time of Sanxingdui, the Yellow River Basin had a subtropical climate. And the Yangtze River Basin to its south, a tropical rainforest climate. So it wouldn't surprise me if researchers, assisted by modern technology, eventually decide that the tusks had come from the surrounding regions, rather than distant lands that, today, have a large elephant population," Hu says.

However, this is not to deny any connection that Sanxingdui might have with those lands, notes the curator. Cowrie shells, as well as small jade and gold pieces, have been found within bronze ritual vessels unearthed from the site, the shells believed to have come from the Indian Ocean.

"Since the late Shang Dynasty between the 12th and 11th century BC, an ancient route had existed that linked the Chengdu Plains with the land to its south and southwest, including modern-day Myanmar and India," Hu says. "The shells could have journeyed to Sanxingdui via this route."

And the silk fabric, depicted vividly as the giant bronze figure's clothing, had probably traveled the same path to foreign lands, more than a millennium before the opening of the Ancient Silk Road in the 2nd century BC.

Elephant tusks lying inside a pit at Sanxingdui. [Photo/THE SANXINGDUI MUSEUM AND THE SHANGHAI MUSEUM]

The ritual jadeware

Back in 1986, a kneeling bronze figure holding a forked blade with both hands was unearthed from the site. Despite his missing head, the figure's general posture, most notably his outstretched arms, contains an unmistakable solemnity befitting the atmosphere of a ritual ceremony.

The blade constitutes a bronze rendition of a type of ritual jade known as zhang, which was being discovered around the same time in relatively large quantities from the site. "Jade zhang had been offered by the Sanxingdui people as a form of sacrifice to the mountains," says Hu, pointing to one unearthed from the site that bears the repeating pattern of man and mountain, the latter having a forked zhang erected at its foot.

"Given the grand, standing figure's presumed role as a chief priest, it was only natural that he held a piece of ritual jade, zhang for example" says Hu.

Possible candidates also include another type of ritual jade known as cong. A cylindrical tube encased in a square prism, the shape of cong, if it was indeed the missing piece of the puzzle, would have fitted the cavity formed by the man's hands perfectly.

It's interesting to note that the jade cong found at Sanxingdui had, in fact, come from at least two disparate cultural traditions — the Neolithic Liangzhu culture centered on the lower Yangtze River Delta, and the early Bronze Age culture of Qijia, which was mainly distributed around the upper Yellow River region in what is modern-day Gansu province.

"Their coexistence at Sanxingdui suggests that the place, rather than being a backwater, was actually a nexus where multiple influences conflated," says Hu.

"To this potent mixture, the Sanxingdui people had added a spoonful of their own cultural ingredients," he continues, pointing to one particular jade zhang shaped like a fish, in the open mouth of which sits a bird.

"This bird is no average bird, it is a cormorant, or fu in Chinese. The combination of a fish (yu) and a cormorant (fu) spells Yufu, the name of a legendary king that had ruled the kingdom of Shu," says Hu. "The same combination was repeated by the engraved patterns on the gold scepter."

The giant bronze tree unearthed at Sanxingdui, with bronze birds perched on its branches. [Photo/THE SANXINGDUI MUSEUM AND THE SHANGHAI MUSEUM]

The bird

One of the few consensuses reached on the Sanxingdui culture is that it worshipped the sun. And one artifact considered central to this belief is a giant 4-meter-tall bronze tree unearthed from the site, upon the branches of which are perched nine bronze birds. (Other bronze trees have also been found, but this is the only one that has been restored so far.)

"A mythic geography book named Shan Hai Jing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas) and dated to before the 4th century BC told about giant trees, upon which sun-carrying black birds reside. Keeping in mind that the words 'Chengdu' appeared multiple times in the book, some have suggested a direct link between the book's description and the bronze trees and birds of Sanxingdui," says Hu.

"There's no denying a bird's place in the cultural and artistic vernacular of Sanxingdui," he says, referring to the many bronze bird sculptures unearthed from the site.

Back in 1986, within the same pit that had yielded the bronze tree — and the grand standing man — archaeologists discovered a bronze bird-man complete with an equine nose, a spread-out tail and talons belonging to a bird of prey.

During more recent excavations between 2020 and 2021, other bird-men were found, one of whom sustains a tall ritual bronze artifact on his head, with his tail dramatically upheld to reach the rim of the bronze.

However, it was the discovery of a small bronze standing man around the same time that had caused a flurry of excitement. Measuring about 20 centimeters high, the man, with similar clothing, facial features and hand gestures, amounts to a miniature version of the giant upright figure, minus the headgear.

Yet, this smaller fellow was holding something: a bird, who had traded its fluffy plume for a more streamlined, easily gripped design, the only whimsical touch of which was a fanciful, ascending decoration on the bird's beak.

"Finally, here's the answer! That was how many people genuinely felt at the time," says Hu, who shares the feeling, if only half-heartedly.

"The smaller figure has certainly provided a key, pointing us in a direction to which little thought had been given previously. But, the discovery has in no way ruled out other possibilities," he says. "In fact, as we speak, a batch of new findings have been made on the site, which hopefully will shed more light on this eternal myth of Sanxingdui.

"Whatever has been, or will be, unearthed from the land always conceals as much as it reveals."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn