An Eccentric Approach

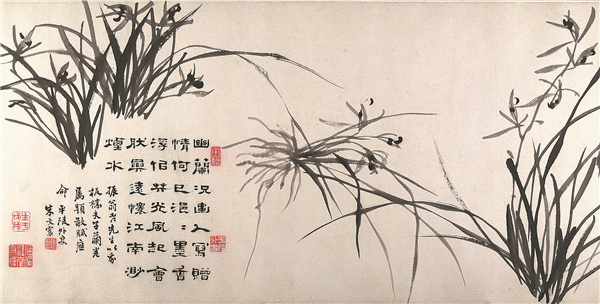

Part of Orchids and Bamboo, painted by Zheng Xie (Zheng Banqiao) in 1742. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Met exhibition shows how famed Chinese artists used depictions of the natural world to comment on society, Zhao Xu reports in New York.

In 1753, 60-year-old Zheng Xie (Zheng Banqiao) left behind his life as a county magistrate once and for all, to engage solely with painting and poetry, and a close-knit circle of like-minded friends known today as the "eight eccentrics of Yangzhou".

Yangzhou was an affluent eastern Chinese city and haven to scholars, painters and calligraphers, disenchanted or not.

The decision was voluntarily and involuntarily taken: voluntarily because Zheng had helped to seal his own fate as a court official by openly disobeying his superior; involuntarily because Zheng, who had spent the first 43 years of his life trying to pass the examinations needed to enter imperial officialdom, was left with no choice — to concur with his superior would mean to close the county granary to starving villagers at a time of great famine.

Zheng, who once wrote that "the rustling of the bamboo leaves outside my abode reminds me of the grunting and groaning of the destitute and the downtrodden", chose to listen to that sound, one that resonated deeply with him. Before departing, he painted a few stems of "skinny" bamboo "for use as fishing poles over wind-ruffled water", according to his own inscription.

If anything, the bamboo rustling proved to Zheng that integrity was vital.

This belief is evident in many of his works, including one recently on display at an exhibition, titled Noble Virtues: Nature as Symbol in Chinese Art, at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In his own inscription, the painter-calligrapher described his work as a "portrait" for a friend who, like the bamboo, harbored the same "hollowed heart", one that's unclogged by worldly pursuits. One cannot help but think that the 49-year-old Zheng was also creating his self-portrait, at a time when many of the trials and tribulations of his life lay ahead.

"When the painting was done in 1742, Zheng was in Beijing, capital of the Qing empire (1644-1911), socializing with members of an elite, literary class, many of whom were scholar-officials," says Joseph Scheier-Dolberg, the show's curator.

Complete disillusionment would not come until a decade later, but the man had already matured as an artist. With his "economical, almost strategic" application of ink — to quote Dolberg, Zheng conjured up orchid flowers complete with pistils and stamens, with just a few strokes and dabs. The orchids' slender leaves echo the spindly stalks of the bamboo, and both find company in rocks, a symbol of constancy in the artistic language of ancient China.

While Zheng's work exudes tranquillity, elsewhere the bamboos are subjected to wind and rain, with wispy tendrils swept up or leaves soaked and heavy.

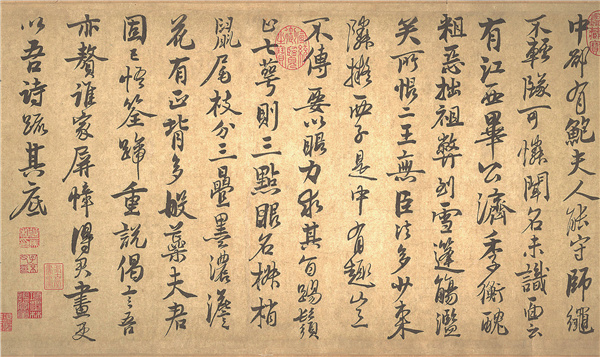

Part of Zhao Mengjian's poems, written in 1260, on painting plum blossoms and bamboo. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Cultural connotations

In Chinese, a bamboo node, or jie, has the same pronunciation as another Chinese word denoting loyalty and rectitude. The association was routinely alluded to by those who considered themselves occupants of moral high-ground in times of adversity.

That adversity could be brought on by the sweeping force of history, whose course is strewn with the casualties of power struggles. The successive emperors of a particular monarchical regime claimed to rule by the mandate of heaven, until that was lost to a contender, often following bloody, protracted warfare. But "a change of the sky", as Chinese would call it, had often failed to produce an immediate change of mind.

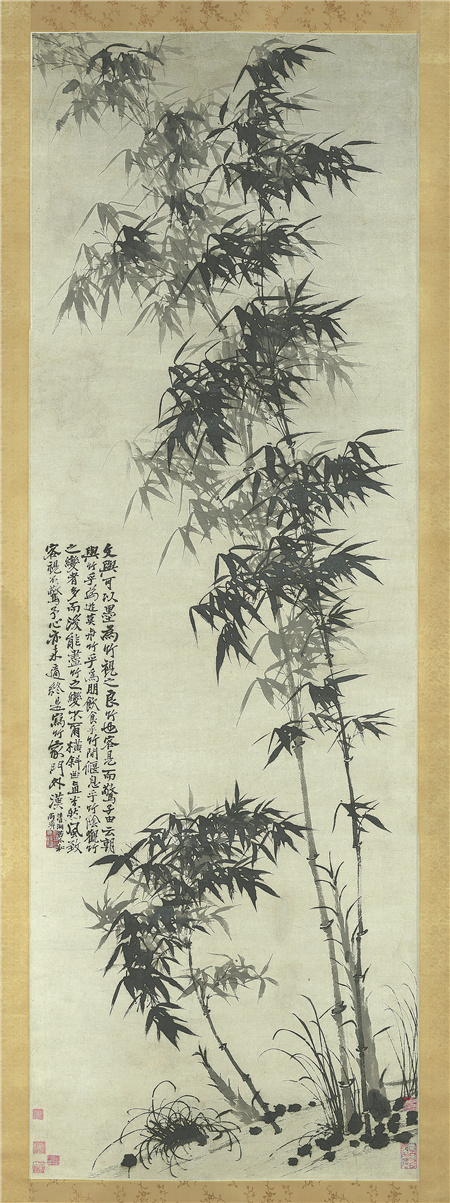

Yang Han (1662-1722) and Zhu Ruoji (1642-1708), both of whom painted bamboos and were featured in the Met show, were born within the two decades during which the ethnic Manchu people from northeastern China defeated the armies of the Ming empire (1368-1644), rode into Beijing on horseback and founded the Qing — the country's last feudal dynasty.

As members of the majority Han people who ruled China in a large part of its history, both painter-calligraphers harbored grievances, not helped by the fact that Yang's father had once served in the Ming court while Zhu Ruoji was the direct descendant of Ming's extended ruling Zhu family.

By filling their bamboo paintings with swooshing wind and spattering rain, the two men highlighted the plant's quality of bending without breaking, apparently inspired by the strength of the reed to offer their own quiet resistance.

Or, to maintain their "public posture and identity" — to use the words of Dolberg — one that allowed them to stay within a circle largely populated by Han scholars who saw themselves as Ming's "leftover subjects".

How steadfastly they had clung to that identity, however, is debatable.

In 1684, a decade before Zhu made that painting, he was given an audience by Emperor Kangxi, who, during a tour of the rich southern part of the Qing empire, stopped by a Buddhist temple Zhu was residing in at the time.

When that experience was repeated five years later in another Buddhist temple during another of the emperor's six southern tours (this time, Kangxi, upon seeing Zhu who went by the name Shitao, was able to recognize him instantly), the man was grateful enough to inscribe himself in a painting he presented to the emperor as "your faithful subject, the monk". He was elated enough to travel from Yangzhou to Beijing in the hope of capitalizing on what turned out to be fleeting fame.

By doing so, the painter had plainly ignored the fact that as a 3-year-old, he was secretly removed from home and taken into a Buddhist temple by a house servant, following the killing of his father, a vassal lord, amid all the rivalry for the throne of an empire which by that time had largely ceased to exist.

In Beijing, Zhu wanted to serve the Qing emperor not just as a painter and was deeply disappointed when the capital's rich and powerful, whom he tried to ingratiate, refused to see him as anything other than someone who could paint.

He returned to Yangzhou in 1690, 63 years before Zheng did the same, where he painted for the next 18 years until his death, leaving behind a treasure trove of works that would greatly influence latecomers, among them the "eight eccentrics of Yangzhou".

In that particular painting displayed in the Met, Zhu quoted famed Song Dynasty poet-writer Su Zhe (1039-1112) commenting on his cousin Wen Tong (1018-1079), who in turn was worshipped as the finest bamboo painter of all time.

Describing Wen as "sauntering and slumbering", "feasting and resting" amid bamboo, Su concluded that "only after much observation can one fully comprehend bamboo's transformation and self-renewal".

Bamboo in Wind and Rain, painted by Zhu Ruoji (Shitao) in 1694. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Painted and written art

But is it only about bamboo? "No," says Dolberg. "Because bamboo is natural, it inevitably led to the understanding of the patterns of nature and the structure of the universe. It's the gateway to understanding the whole thing."

Yuan Dynasty painter Li Kan (1245-1320), whose work was featured in the Met show, must have thought so. Having traveled the country studying different varieties of bamboo, the man emerged to write his own treatise on the plant, and to give them highly realistic painterly renditions in which the sun-dried, faded tips of the leaves were treated with a graded ink wash.

By this time, bamboo had long entered the canon of literati painting and as such should by no means be treated lightly. That's why painterpoet Zhao Mengjian (1199-1264) had composed several long poems on how to paint bamboo and plum blossoms — the latter, blooming in late winter and early spring, contains an apparent symbolism for those who believed that "every winter has its spring", to quote a US writer.

In case one doesn't know, the term "literati paintings" loosely applied to works by the society's highly educated members who generally approached painting in the same way as they did calligraphy and poetry-writing, often as expressions of subtle, permeating thoughts.

Zhao, a master calligrapher, later transcribed these poems, composed on disparate occasions, onto a long, horizontal scroll of artwork that can be viewed as one holds it in hand and gradually unrolls it from right to left.

The piece's inclusion into the Met's show serves a deliberate point, says Dolberg. "Bamboo painters would often talk about the fact that the strokes they used to paint bamboo are quite similar to the ones they adopted for calligraphy." That is, similar in appearance, same in spirit.

Think about the animated, ink-soaked brush, from under which elegant characters are fast emerging alongside plum blooms and buds whose depiction requires "barely connected" strokes as fine as "a bee's whisker", to use Zhao's own words. In both cases, spontaneity comes from study, and dynamism from deliberation.

Of the eight colophons attached to Zhao's piece, five were composed by people who were closely associated with Zhao and with one another, between 1267 and 1288. (Colophons here refer to commentary writings usually made by those into whose possession the original piece had fallen. Either taking up a place within the piece or attached to its end, colophons are often works of calligraphic art in their own right and accumulatively provide a record of its history.)

Affectionate posthumous tributes, the writings have collectively painted an image of a man whose devotion to art never tempered with his generosity when it came to gifting friends with paintings. He was sorely missed by his men.

Another piece featured by the show and drenched in similar communal spirit was an over 6-meter-long hand scroll painted in 1505 by Lu Fu, known by his contemporaries as the plum-blossom painter. It was commissioned to commemorate an afternoon a man named Zhang Ling spent with Shen Zhou (1427-1509), a Ming Dynasty scholar who by that point had reached the pinnacle of his fame, as a man who was prescient enough, noble enough and — as some might like to point out — wealthy enough to have never attempted to serve the government.

After the painting's completion, Shen inscribed a poem on it, and was followed by other prominent members within his literary clique who played a game by following the same rhymes — we know the story because one of them had recounted it briefly on the painting.

Providing a magnificent example for the interplay between painted and written art, these inscribers nestled their calligraphy between the flower-laden boughs, sometimes allowing one particular stroke to dally with a delicate petal, as Shen had done.

Like the jade-like petals shimmering in flooding moonlight, the painting responds to the glowing additions of these big names through its own beauty. Rather than painted on, the white flowers and the snow that chills their fragrance were brought forth by the painter who left these areas untouched, choosing instead to deluge the background in an icy, consistent blue that contains no brush marks and never encroaches upon the flowers that seem to have transpired out of it.

"How Lu Fu did it was an ongoing mystery. Most scholars believe that he must have applied a certain substance — something nonabsorbent mixed with water — to the petal areas before applying the blue, which, as a result, would simply stay out of those parts," says Dolberg. "But this would have been very difficult to manage over such a long, complex composition."

Equally if not more remarkable is the fact that the painting, which by virtue of being a hand scroll is supposed to be viewed bit by bit, was actually painted with its entirety in mind, and therefore is best appreciated completely laid out, as it was displayed at the Met.

"If you step back and look at the whole thing together, you start to realize that instead of comprising multiple vignettes, the painting is in fact an up-close view of a horizontal slice of one blooming tree, with its sprawling branches coming in and out of the frame all the time," says Dolberg.

"It's very rare for an ancient Chinese painter to think of the hand scroll as a kind of long slice of a larger scene, and give it a monumentality as Lu did here."

Part of the scroll work created by Lu Fu in the early 16th century and inscribed by some of his contemporary scholar-poets, including Shen Zhou, whose calligraphy appears on the left. [Photo provided to China Daily]

'Ink play'

In contrast to such opulence is an album of plum blossom paintings of Li Fangying (1696-1755), marked by a simplicity bordering on abstraction. If anything, the abbreviated brush-strokes, exuding both verve and ease, remind one of Zheng and his orchids. The two's comparability doesn't stop here — Li also stepped down from his position as a county magistrate after repeated clashes with corrupt superiors.

"To sell paintings in Yangzhou and grow old with Li (Fangying)" was what Zheng had envisioned for himself and his friend. However, Li never grew really old. He died in poverty at the age of 58 — 12 years before Zheng did at 73. "It is not my life but my painterly hand that I mourn" were his final words.

In the Met, Li and Zheng reunited with another two members of the "eight eccentrics of Yangzhou", represented respectively by a bamboo painting and an album of plum blossoms. (All exhibits can be checked out at the museum website.)

Jin Nong (1687-1763), the plum painter of the two, described in one of his whimsically modern renditions how a monk from a nearby mountain temple brought him much-needed rice in exchange for a "fun ink work".

It is no coincidence that more than one and a half centuries after Zheng died in 1766, Wu Changshuo, a renowned painter-calligrapher, would inscribe the title sheet of his Met-showcased bamboo-and-orchid piece with two big Chinese characters literally meaning "ink play".

Zheng, who famously remarked that "in painting, I follow no rules and set no rules", had without doubt conducted himself with enough irreverence to be considered idiosyncratic or playful.

But he did have something — indeed certain people — uppermost in mind.

On one of his later works he wrote: "Whatever I have painted is not meant for men who luxuriate in life, but rather for those who experience its pain and pathos."