Treasures of Tibetan History and Culture

Part of Bunian Tu painted by Yan Liben, Tang Dynasty, 38.5×129.6cm, collected at the Palace Museum. courtesy of the Palace Museum

Humans have been inhabiting the Himalayan mountains between the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the South Asian subcontinent since remote antiquity, and the region is known for its brilliant and profound plateau culture. The 200-plus cultural relics now on display at the Capital Museum in Beijing testify to the fact that the snow-capped plateau has never been isolated from the outside world. Eons of cultural exchange and integration conducted with the surrounding areas and the central plains, where the Han civilization originated, have tremendously enriched and diversified Tibetan culture.

Recently, many precious Tibetrelated cultural relics were put on display for the first time at the Capital Museum in Beijing. The exhibition has already attracted numerous visitors with items such as Bunian Tu, one of the 10 most celebrated surviving paintings from ancient China, a huge embroidered thangka featuring Yamantaka (a Tibetan Buddhist deity) from the Jokhang Monastery, the earliest decree issued by the Qing court to Tibet and the first officially collated Tibetan Tripitaka.

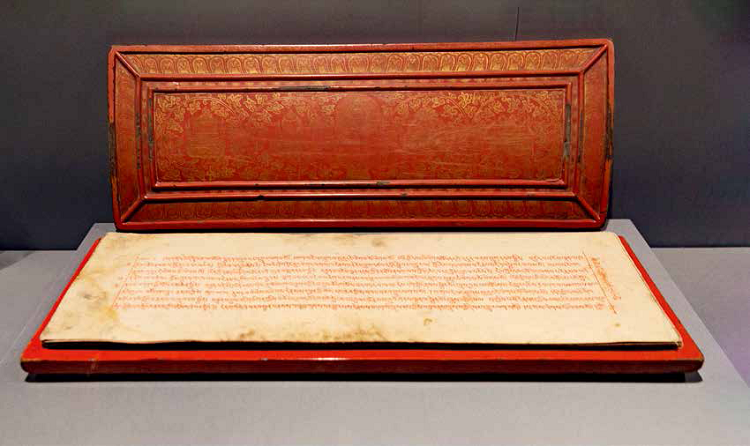

An edition of Kanjur Tripitaka from Emperor Yongle’s reign, Ming Dynasty, 72.5×26.5cm, held by the Potala Palace Treasure House.

Witness of Cultural Exchange

On February 27, 2018, the “Tibetan History and Culture” exhibition kicked off at the Capital Museum, featuring 216 extremely rare cultural relics related to Tibet.

Themed on Tibetan cultural exchange, many exhibits were borrowed from 13 sacred religious sites in the Tibet Autonomous Region including the Jokhang Monastery in Lhasa and the Tashi Lhunpo and Sakya monasteries in Xigaze. None had been previously unveiled to the public.

More than 180 of the exhibits were provided by museums and cultural heritage institutions in Tibet. A staffer of the Capital Museum stressed that many of the items from Tibetan organizations shouldn’t be missed, including a local Neolithic twin pottery container, a piece of silk featuring the Chinese characters “Wang Hou” (prince and marquis), a magnificent gold mask from the Zhangzhung Kingdom and a huge embroidered thangka from the Jokhang Monastery that dates back to the Yongle reign of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Highlighting the important role of Tibetan history and culture in the development of the multi-ethnic community that is the Chinese nation, the exhibition is split into four sections: Origins of Civilization, Major Links on the Plateau, Buddhist History in Tibet and Reunited as a Family.

The plentiful unearthed archaeological relics from Tibet dating back to as early as the Late Paleolithic Age (between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago) show that since ancient times, humans have been living and prospering on the snow-capped plateau.

Han Zhanming, director of the Capital Museum, explained that the four sections are designed to trace the formation of the local cultural identity and the national identity by presenting the history and culture of Tibet as well as examples of cultural exchange between Tibet and the surrounding regions including China’s inland areas. Curators hope to expound on the fact that Chinese history was created by all the ethnic groups of the country.

An edition of Kanjur Tripitaka from Emperor Yongle’s reign, Ming Dynasty, 72.5×26.5cm, held by the Potala Palace Treasure House.

Bunian Tu: Historical Testament to Harmonious Han-Tibetan Relations

Of all the exhibits, Bunian Tu is one of the brightest stars. Visitors from near and far have flocked to the exhibition just for a glimpse of the masterpiece. The work, now part of the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing, has rarely been shown to the public even at the Palace Museum, according to the museum’s director Shan Jixiang, who visited the exhibition on its opening day.

The 1.3-meter-long silk scroll is generally believed to have been painted by Yan Liben, an artist and official of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Its gorgeous colors, smooth lines and delicate composition make the painting one of the most representative works of the Tang Dynasty, reflecting the close connections between the Tang court and Tibet, which was then known as the kingdom of Tubo.

Based on a historical event, the painting depicts the scene of Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty meeting Gar Tongtsen Yulsung, envoy of Tubo ruler Songtsen Gampo. Songtsen Gampo had proposed a marriage alliance with the royal family of Taizong. Princess Wencheng, a member of the Tang royal clan, was subsequently betrothed to the Tubo ruler.

The tale depicted in Bunian Tu is well known in China and an important historical milestone for Han-Tibetan relations. When Princess Wencheng went to Tibet, she brought a large volume of silk, classical books, seeds and hundreds of craftsmen from various sectors. Her arrival effectively brought advanced culture and production technology of the central plains to the plateau, which greatly promoted the development of politics, economy and culture in Tibet.

Subsequently, the children of many Tubo nobles were sent to Chang’an, then the capital of the Tang Dynasty, to study. For a long time since then, relations between the Tang court and the kingdom of Tubo remained close and harmonious. The painting is a historical witness to the friendly exchange between Han and Tibetan ethnic groups, with immeasurable historical value.

According to the exhibit description, the scroll is generally considered an authentic painting by Yan Liben, but some scholars believe it a facsimile of Yan’s work from the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). The painting is scheduled to remain on display for just two months because time has left it extremely delicate.

A pair of sandalwood suonas (Chinese woodwind instrument) decorated with gold and jewelry, Qing Dynasty, 58cm tall, caliber diameter of 15cm, held by the Potala Palace Treasure House.

More Highlights

The magnificent Zhangzhung gold mask and a piece of silk featuring the Chinese characters “Wang Hou” are the two most representative relics borrowed from the Tibet Autonomous Region.

In the section “Origins of Civilization,” a gold mask dating back to the third century, unearthed in Ngari Prefecture of the Tibet Autonomous Region, was placed in the center of the exhibition hall. Similar in size to a real face, the mask includes a crown above the facial part and is decorated with many layers of fabrics in the back. The gold mask was used for burial in the Zhangzhung Kingdom (500 B.C.-625 A.D.), making it about 2,000 years old. During that period, it was a popular custom to cover the faces of the dead with a gold mask in several Eurasian countries. And similar masks have been found in Nepal and India. Research shows that as early as 2,000 to 1,800 years ago, western Tibet established close ties with what is now the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region as well as countries on the South Asian subcontinent. Tibet conducted extensive exchange with the central plains and grassland areas of Central Asia.

The silk featuring the Chinese characters “Wang Hou” is now broken and stained after so many years, but the brown decorative patterns on the brocaded item and the blurry bird and beast designs give viewers a glimpse of its original glamor.

Upon discovering the Chinese characters “Wang Hou” surrounded by the bird and beast patterns, archaeologists determined that this kind of silk would likely be produced on the central plains of China.

This piece of silk is the earliest sample discovered in western Tibet so far, but silk pieces with similar patterns have been unearthed in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region and other areas. “The characters on the brocade were written in a font similar to the clerical script, which indicates that it was produced on China’s central plains before being transferred to Tibet, which evidences communication between Tibet and the inland areas at that time,” explained Zhang Jie, curator of the exhibition.

“With these relics, we want to correct the common misconception that Tibet was a relatively inaccessible place in ancient times due to harsh geographic conditions,” Zhang added.

“In fact, it has been open to the outside world since remote antiquity,” he continued. “Since the Stone Age, Tibet has been influenced by the civilization of the Yellow River Basin and has been absorbing the achievements of civilizations in the surrounding areas and countries, which promoted people-to-people exchange.”