Light at the edge of darkness

Zhang Lian in his native home in Yanchi, in Northwest China's Ningxia Hui autonomous region, at sunset. KUANG LINHUA/CHINA DAILY

'Peasant poet' Zhang Lian, whose words paint vivid pictures of his remote, vast home, has captivated and inspired professors and plumbers alike, Zhao Xu reports.

One early morning in April 2018, Liu Keming, having been "jostled awake", stepped outside of her carriage on the night train to be "greeted by the instant coolness of the steppe air mixed with that sweet, earthy smell of the alluvial plains".

That's how she recounts the experience in the introduction to Twilight, her translated anthology of works by Chinese poet Zhang Lian, which was published in September 2022.

Her destination was Yanchi, a small county sitting in Wuzhong, Northwest China's Ningxia Hui autonomous region that borders the Inner Mongolia autonomous region to its north. The land, where the desert steppes meet the loess plateau (more commonly known in China as the yellow-earth plateau), dictates for the locals a half-farming, half-herding lifestyle, one that Zhang had reluctantly embraced for many years.

The aim of the trip was for Liu, a professor of linguistics and world literature at the City University of New York, to absorb "the color and the light", which she had discovered upon her first encounter with Zhang's words while sitting in her own home on the East End of New York's Long Island, a place drenched in both.

But the differences couldn't be greater.

"This is where the poet Zhang Lian lived and wrote all these years, where the vast expanse of emptiness, blue sky above, yellow earth below and a dark road cutting right through it, reminds one of a (Mark) Rothko painting," Liu wrote of her first impressions of the arid, rain-starved landscape.

Of all things, Liu was struck by its expansiveness — previously unknown to her, as she grew up in Chinese cities before leaving to pursue her studies at Columbia University in 1987. "The sight filled me with pride. Immediately I understood Zhang's love for it," she says.

"In Village 39/by a large alkaline lake/tufts and tufts of purple/form a patch of twilight," wrote Zhang in A Patch of Falling Color, originally titled Twilight, referencing that special time of day, just like all the other poems in the anthology.

"I've always believed that the twilight is infinitely more beautiful than beams of the rising sun. Why? Because it's radiant, but at the same time warmer, gentler, calmer and therefore a lot more soothing," says Zhang, who, in another poem, sauntered on the village road "with a bag of twilight and a donkey".

And when he talked about "gathering water in twilight" in yet another poem, one gets the feeling that he was gathering twilight in water.

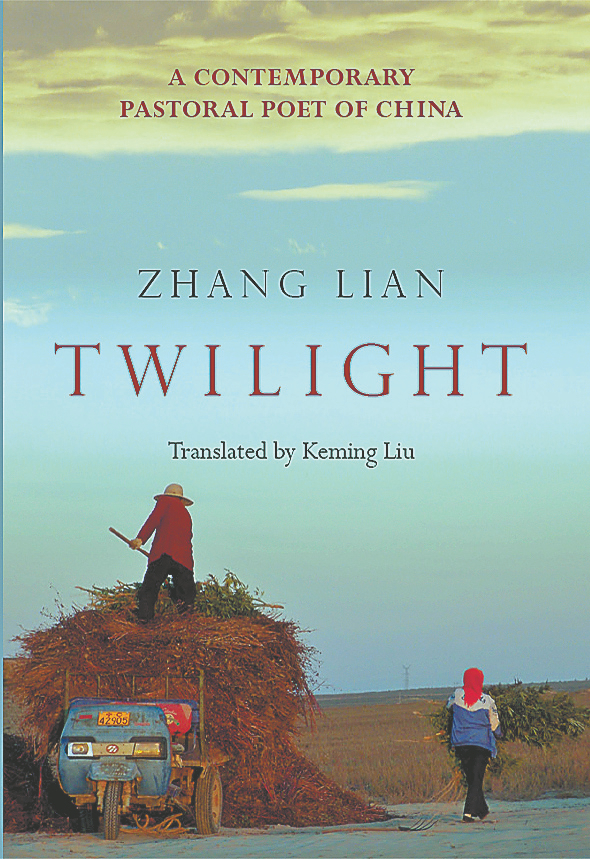

Twilight, a collection of Zhang's poems, translated by Liu Keming. CHINA DAILY

Magnitude of hardship

In 1993, Zhang gave up his job as a substitute teacher at the village school and moved back to his native hamlet to be a potato farmer-cum-shepherd. With his little rammed-earth house — the house has a brick facade — sitting at the western end of the hamlet, Zhang often found himself "entering that patch of splendor" as he herded his sheep home at the end of a long day.

"Those were moments of tranquility, for daydreaming and contemplation," says Liu.

But that's not all. "Writing is my form of resistance against life," reflects Zhang, who lived there with his wife and two children on a monthly income of about $70 until 2005, when he returned to the Yanchi county center to open a bookstore.

"I failed four times to pass the exams for high school back in the 1980s. And that was the end of my formal education," Zhang says.

The scarcity of educational resources, and his addiction to words and the consequent neglect of other subjects are certainly part of the reason. Poor health didn't help either. At age 10 and suffering from acute hepatitis, Zhang was taken by his father to the nearest hospital 20 kilometers away on a mule-pulled wooden plank cart. On their way back home, upon entering the hamlet, the boy, lying flat on the slow-moving vehicle, became spellbound by the heavenly blaze ignited by the setting sun.

"The world's dusk/pulls down its curtain here/and my heart is reluctant to depart," he wrote many years later in another poem, also included in the anthology.

"The twilight consoled me like my mother. It constitutes my spiritual home, to which I'm on an eternal return journey," says Zhang.

"The magnitude of hardship" is what Liu believes underlies Zhang's poems, although it is only referred to occasionally and obliquely. The fact that he had lived a life of monotony, surviving in one of the country's poorest and least inhabitable regions, has only sharpened his senses: Whatever little color he saw in his surroundings, he seized it, distilled it through his creative mind and then let it suffuse his poetry.

"He puts color in a world without much of it. He paints with his words and vision," says Jack Gismondi, who was just "Jack the plumber" to Liu until one day in October 2018, half a year after the latter's meeting with Zhang.

"I was staring at a painting at an art show held in my neighborhood, and there it was. Hanging right beside a piece of art was the writing of a man who had been fixing our showerheads and toilets all these years," Liu recalls.

Liu Keming (center) and Zhang visited his former abode during Liu's visit in April 2018. YOU QIHONG/FOR CHINA DAILY

That was actually the very first time Gismondi, who writes under the name Eli Stoneman, was asked to produce something to echo the theme of an art showcase. Early this year, Gismondi came up with a short story based on a walk he had taken with his step grandson a long time ago, for an exhibition titled East End Light: Then and Now.

"Reflective light was everywhere, on the trees and leaves that lay upon the ground and on the white pine needles sprinkled amongst the bare oaks, hickories and maples. It was a glittering shimmering feast for the eyes," read the piece, on display alongside paintings inspired by the unique quality of the area's light and atmosphere.

The sentences may have called to Liu's mind a few lines from Zhang's poem The Hunchback: In the tree branches by the house/a touch of red, moving/carrying with it the peacefulness/and a few hunchbacked men.

"Explaining his use of the hunchback imagery, Zhang Lian related how, reading profusely to quench his thirst for outside information ...he came across Charles Baudelaire's Chacun as Chimere (To Each His Own Chimera)", Liu wrote in an accompanying note to her translation of the poem.

Depicting a group of burdened men trudging along towards some unknown destination, the 19th-century French poet wrote, "... beneath the splenetic cupola of the sky, their feet plunged in the dust of a ground as desolate as the sky, they made their way with the resigned expression of those who are condemned to hope always".

"Frustration and hope, they are like night and day," says Gismondi, who was recently given a copy of Twilight by Liu. He has noticed some remarkable parallels between Zhang and himself.

Neither attended college and both were "taught by masters", to use the words of Gismondi. These included English romantic poet Percy Shelley, and American poets Emily Dickinson and Robert Frost — the last being a peasant poet who "transformed daily chores on his Vermont farm ... into meditative poems of astonishing beauty", to quote Liu.

Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation, a fact that has spoken powerfully to both men.

"Herding is a solitary endeavor — Zhang must have spent an awful lot of time talking to himself, and that voice has come across through his poems," says Gismondi, who has penned two full-length novels and a collection of short stories. "I talk to myself all the time while I'm working. That's where the ideas come from when I sit down to write — the time I spent as a plumber, working alone."

Zhang Lian in front of his little house in his native hamlet, where he lived between 1993 and 2005. KUANG LINHUA/CHINA DAILY

Unfiltered and intuitive

The fact that Zhang, who knows not a word of English, was able to draw immense inspiration from those Western writers came as a surprise to Liu during her 2018 trip. More than anything, it convinced her of the meaning of her translation, of which she had remained highly doubtful up to that point.

"When I was in university in China, I read the Chinese translation of Henry James' 1880 book Washington Square. Later, after my arrival in New York in 1987, I made a point of visiting the square, located in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan. To my great disappointment, not much resemblance were to be found with the book, and, naturally, I blamed the translator and started to distrust all translations," says Liu.

Fully aware of the pitfalls of her task, during what she called "the most intense period" of the three years between 2018 and 2021 that she spent translating Zhang's poems, Liu was engaged in frequent WeChat exchanges with the poet on a daily basis.

"I probably wouldn't have devoted that amount of time to it if not for the pandemic. All that back-and-forth between us has allowed me a deeper look into the mental and emotional worlds of Zhang, who was surprisingly simple and sincere, and was nearly devoid of bitterness or cynicism, despite having overcome great adversities — both as a man and a poet," Liu says, alluding to his poems being interpreted by some literary critics in China as having anti-consumerism and anti-urbanization underpinnings.

"That to me would be their projection. Of course, Zhang wouldn't feel at home living in the city, but that doesn't mean he holds anything against the idea. He loves his land, and that love is passionate, intuitive, unfiltered."

Zhang remembers spending a snowy night at a friend's town center house around 2002. Unable to sleep, he walked onto the streets, only to find muddy vehicle tracks crisscrossing what would have been a thick white carpet. "The snow was being crushed and I could feel its pain," he says.

The reason he was there was to sell his self-published poetry collections, often by knocking on the doors of local cultural organizations. "Believe it nor not, 100,000 copies have been sold this way since 2000," says Zhang. "China, of all countries, has a history of poetry and a respect for poets."

That is something that Liu has always intended to convey to those around her. After the publication of the anthology, she was invited by her neighborhood library to give a lecture on the book. "People came up to me afterwards saying that China comes alive through the lines in the book. Even those who have been to Beijing and Shanghai asked if I could take them to see the country's vast hinterland.

"Throughout its history, China has had its fair share of pastoral poets, yet most were members of the literati class who approached their rural subjects with a sense of escapism, sometimes during forced or self-imposed exile. Zhang is different — he belongs, and therefore constitutes an antithesis to any pastoral idealism," Liu continues. "Unlike Shelley, and his fellow 19th-century English poets, Zhang's relationship with the land is characterized not by romanticism, but by a solid, true love."

The professor, who helped to bring the Confucius Institute to her college at the City University of New York, and served as the program's director from 2018 to 2022, traced Zhang's literary realism all the way back to Shijing, or The Book of Songs. Of its 305 works dating from the 11th to 7th centuries BC, 160 are believed to originally have been folk songs created by peasant-laborers.

For Gismondi, Zhang's depiction of his native land reminded him of the Great Plains of America, where, to use his words, "one has nothing but their surroundings". That sense of loneliness had once owned Gismondi, who spent a large part of his 38-year-long marriage taking care of his wife, who was mentally ill, until her passing two years ago.

"When I was in my 20s, I wanted to be a writer, but then life got in the way and I gave it up. Now it has come back to me," he says. "Zhang and I, we live in our own small worlds and probably will never meet. But it would be great if we do."

Back in February 1972, 12-year-old Gismondi watched in amazement as scenes of Chinese streets, with their endless flow of bicycles, were streamed into every US household during President Richard Nixon's historic visit. For him, Zhang seems to belong to a China that's more distant and more ancient.

Vestiges of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) Great Wall in Yanchi. CHEN JING/FOR CHINA DAILY

And, in a sense, he's right. Today, vestiges of the Great Wall, constructed during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), can still be seen rising slightly from the yellow ground of Yanchi, like the scaly back of an armored dinosaur that has fallen into a deep slumber. They are "the tail end of the Great Wall", according to Liu, the markers of a place where Zhang had lived and saw himself "becoming/a speck of twilight/by the tail of each bright day".

Ever since their meeting there in 2018, Liu has been thinking about returning. "He was solidly built with a square jaw and large hands, thick from years of labor," she wrote of her meeting with Zhang at the Yanchi train station. That was before the two sat down to talk in Zhang's living room.

"His voice is authentic. He's a real flower, growing from the cracked earth," she says.