Creating of an Eternal Audience

Long life and colorful career of artist Huang Yongyu are presented as his farewell gift to the world, Lin Qi reports.

Huang drew a remake of his own design of the Golden Monkey stamp, issued in 1980, which attracts admirers to the National Art Museum of China exhibition For So Long, and Colorful in Beijing. [Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

In an article he wrote in 1979, Landscapes Under the Sun, the prolific artist Huang Yongyu (1924-2023) recounted anecdotes about his uncle-once-removed, Shen Congwen (1902-88), a writer and scholar of repute, and how his attitude toward life and academic research had influenced his own.

At the end of the article, he wrote: "What a long life (Shen) lived, and (his experiences were) so rich, and colorful."

Today, Huang is also regarded as a prominent figure in art and culture, whose life and career were, like Shen's, long and substantial.

A phrase from his commentary about his uncle, For So Long, and Colorful, has become the title of an exhibition of his work being held at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing until Thursday.

In 2013, Huang held an exhibition at the National Museum of China to commemorate his 90th birthday. It was an all-encompassing show to display his accomplishments in painting, design and literature — the artist was also an avid writer who published dozens of novels and collections of essays and prose articles.

The current exhibition at the National Art Museum is a show of 159 ink paintings, all made after he turned 90.

It is not billed as a retrospective — the usual practice for a late, accomplished artist — but per Huang's request, as a show of his "latest work". It is one he had planned for some time.

"None of the paintings in the show will have been seen before in art and cultural circles," he once said. "I'm pretty serious about making it happen."

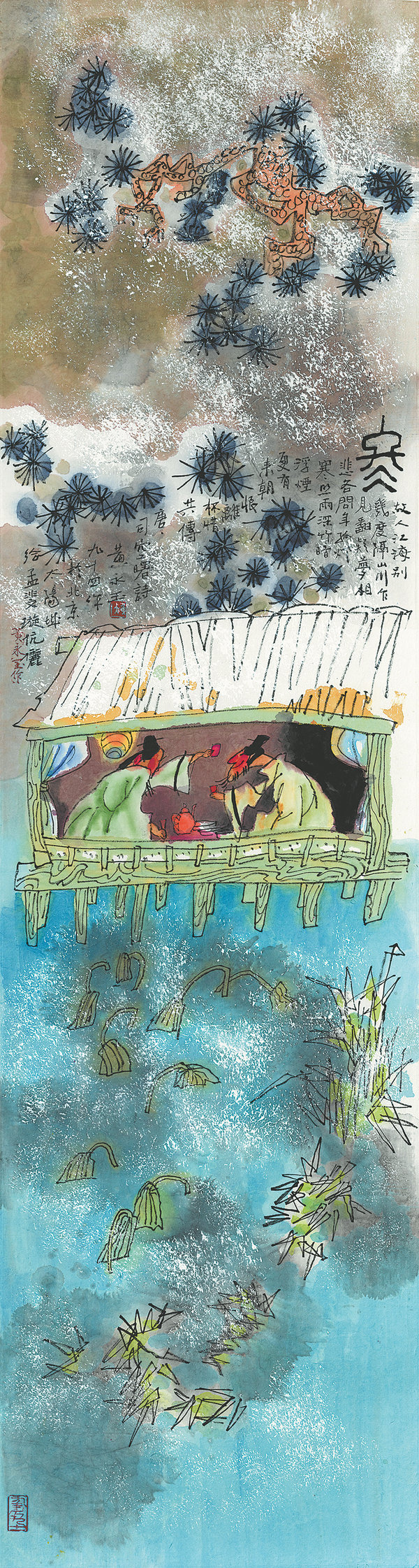

Winter by Huang Yongyu. [Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

Huang died on June 13, 2023, at the age of 99. His farewell to the world was quiet. His family announced his death in a statement released the following day, and no memorial service was held.

In an earlier televised interview, Huang envisaged his centennial exhibition, saying, "It will show 100 paintings, to celebrate the 100 years I have lived. I will show work in which I've invested all my energy. I will be doing my best, but maybe the pieces will not be perfect as far as the audience is concerned. But hopefully, people will feel they are not bad, and that will be enough for me."

The earliest painting currently on show was finished in 2015, and the most recent was completed a few weeks before his death, demonstrating his lifelong passion for art, and for sharing that pleasure with the public.

The paintings are vividly colored, often highly saturated, and feature recurring motifs from his work popular with his audience over the years, such as lotus flowers, immortals and animals.

They are also a reiteration of his ambition to create, which lasted until the final moments of his life. Several paintings on show are over 1 meter in length, some even over 2 meters — quite a challenge for a man of his age.

Born in Changde in Hunan province, Huang left home in his early teens to earn a living doing a variety of jobs, including stints at ceramic factories, primary schools and theater groups — and also learned to paint and to make woodcuts.

He gained the most from his wartime experiences, the social vicissitudes of the 20th century China, and from the people of different backgrounds he met along the way.

According to Shao Dazhen, critic and professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where Huang taught for decades, his art and writing reflects "the realities of the world, in a straightforward manner, with no pretense".

"He loved people and he loved life deeply, but he expressed this in a peaceful way. He spoke for the public, when he painted and wrote," Shao says. "His work is sincere, interesting and appealing. It is unparalleled."

Huang Yongyu [Photo provided to China Daily]

Physically confined to his home in suburban Beijing in the later stages of his life, Huang was not able to travel as much as he liked. Instead, he turned his shrewd gaze on small things within his reach; the potted flowers in his study, the new plants in his courtyard, and shrimps brought by friends. He examined them at length, lost in thought and then expressed what he felt with ink and color.

Wu Hongliang, director of the Beijing Fine Art Academy, which has held several exhibitions for Huang, says that the artist saw "a miniature universe" in the small lives around him, and celebrated them in his work.

"One feels the various dimensions he used to understand the world, which were not only based on an accumulation of knowledge, observation and experience," Wu says, citing one of the paintings on display depicting a spider and a butterfly trapped in its web, a scene Huang observed one day.

"He drew the scene and related it to how one makes judgments in life. He always worked hard to enrich his knowledge of the world."

The exhibition also zooms in on Huang's mastery of baimiao (plain drawing), a technique he favored when painting in the classical Chinese style.

It relies on the artist's ability to control his brushes and paint smooth, changing lines to finish a drawing, with no other color but ink.

Huang's depiction of Li Shizhen is a fine example of this kind of work. In it, Huang painted dense lines all over the paper to build up an image of the 16th-century medical scholar and author of Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu), surrounding him with dozens of plants, insects and other materials of traditional Chinese medicine that he is known to have researched.

"Literature ranks first in my life, before sculpture and woodcuts, and painting comes fourth," Huang once said.

He read and wrote extensively. "My advice to young people is do not waste time, read a lot, let books be your guide."

These preferences are also evident in the paintings on display.

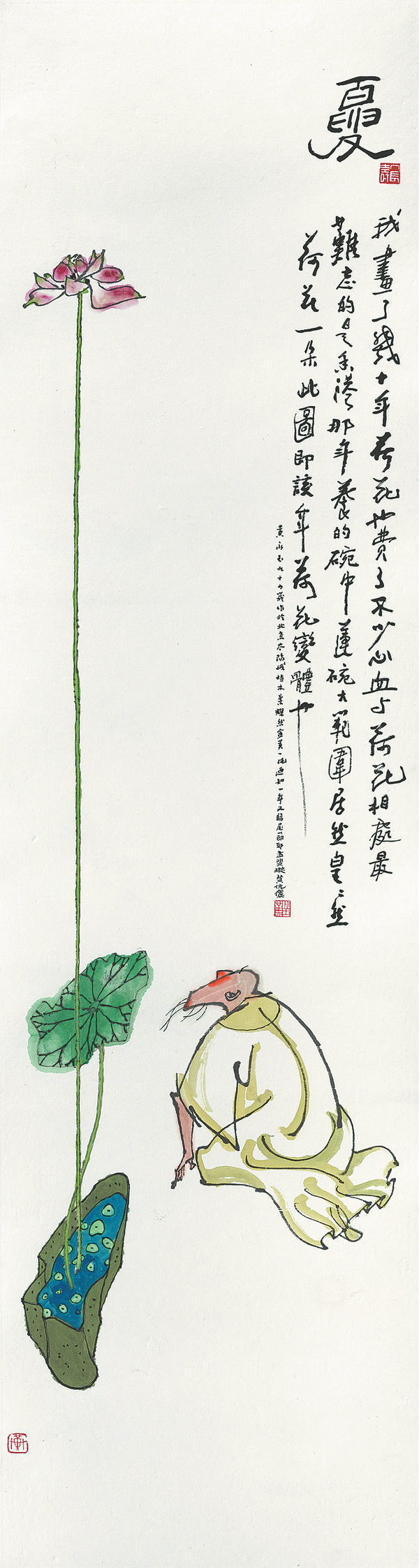

Another of Huang's work, Summer. [Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

Adding short poems or brief commentaries is one characteristic of classical Chinese paintings.

Huang reinforced that tradition by extending the length of the texts — his commentaries on paintings are often of hundreds of characters in length, enough for an essay.

Wu says that Huang's writing is full of the wit and humor for which he is known, melded with a down-to-earth manner and sense of calm that pleases both the eyes and minds of his readers.

"The reason that he did so many baimiao drawings and wrote lengthy commentaries on paintings was probably because he wanted to tell people that even at his age, he still had good control of his brushes, and retained his pursuit of detail," says Lei Zhenfang, a close friend and former art director of Rongbaozhai, the centuries-old cultural brand of Beijing.

In 1953, then a teacher at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Huang was dispatched by the school to research traditional woodblock printing at Rongbaozhai, where the technique was well preserved. Lei says that Huang studied for more than two months and learned under the guidance of artisans he also befriended.

He adds that all his life, the artist sought change and dared to confront challenges, and as a result, contributed to the revival of Chinese art.

"He never felt satisfied with himself. He often said, 'If I do one more drawing, I will do better than with this one.' His pursuit of freedom in art was motivated by his attempt to make breakthroughs."

Huang once said that those who paint are doomed to be alone.

"The painter needs to deal with everything around him in the world, and needs to confront changes, all the while keeping his world of art quiet and peaceful with utmost restraint."