Old Tale, New Admirers

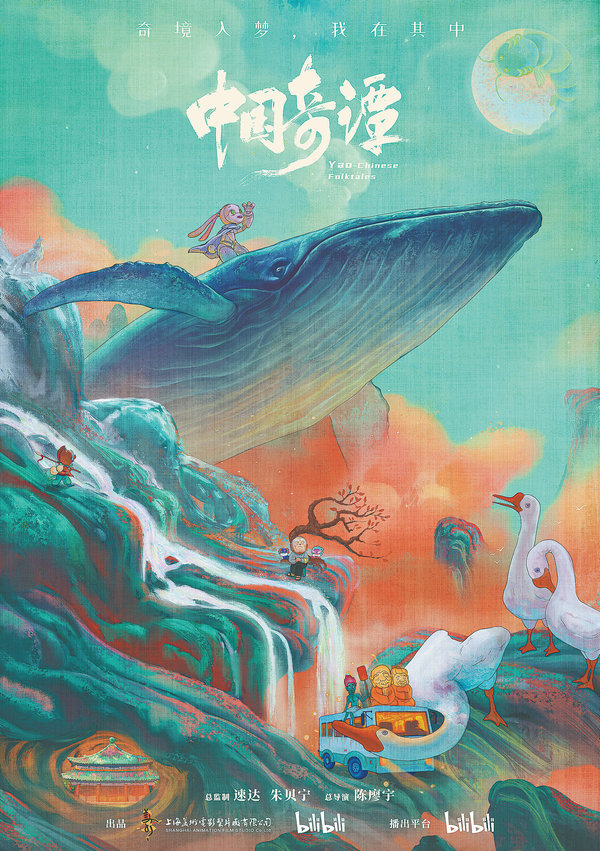

Traditional Chinese painting style is one of the major features in the animation series Yao — Chinese Folktales. [Photo provided to China Daily]

A new adaptation of Chinese mythological stories has won the heart of audiences with its distinctive style, intriguing imagination and resonating narrative. The animation series, Yao — Chinese Folktales, which premiered on Jan 1, has gained more than 110 million views and a score of 9.9 out of 10 on video-sharing platform Bilibili.

The series, co-produced by Shanghai Animation Film Studio and Bilibili, is a collection of 20-minute short films, consisting of eight separate stories featuring monster-like characters, or yao in Chinese.

The collection, which ranges from ancient stories to science fiction, from emotional connection with hometowns to romantic love, and from life themes to questions for humanity, presents Chinese culture and philosophy.

According to Chen Liaoyu, general director of the animation, the theme is folklore and myth which are open for the creators to express their own understanding, and there is no limitation in stories and style.

Chen says myth can be from ancient times, as well as today and the future. Myth is actually human imagination of something unknown or a projection of inner desires.

Even the images in myth are figurative expressions of a particular aspect of humanity, he says.

The animation series Yao — Chinese Folktales includes eight short films and covers a wide range of subjects, from ancient mythological stories to science fiction. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Style and innovation

The animation covers a variety of art styles and production techniques, from traditional two-dimensional paper-cutting to modern technology of computer graphics, as well as innovative combination of sketching and Chinese ink-and-wash painting.

According to Li Zao, general producer of the animation, the project, which took over two years to complete, has its own strong experimental and innovative feature on art styles.

During the preparation of the eight short films, Li says their team had encountered various problems, such as the coordination of all the teams and the massive workload in the late stage of the production, but all were solved eventually.

As the directors were from different backgrounds, such as advertising, cartoon, animation and education, each team needed help in different parts. From ideas and stories to the production, for each step Li's team offered help accordingly.

"Each team was passionate about their work, and they continuously optimized their content," Li says.

The favorable comments and related Sina Weibo's hashtags exceeded the expectations of the creative team.

"To a large extent, this contains both the audience's recognition of our work and their expectations of Chinese animation," Li says.

Some viewers say the animation has certain thresholds in aesthetic appreciation, which Li totally agrees with. She says that besides catering to the audience, the team also wanted to guide them to appreciate different types of work.

"From the audience feedback, we think the public can accept and are willing to see various styles," Li says.

Li says the animation has tried to integrate the content to show that traditional Chinese mythology can resonate with modern people. It's a multi-perspective interpretation of Chinese aesthetics by the creators, she says.

The animation series Yao — Chinese Folktales includes eight short films and covers a wide range of subjects, from ancient mythological stories to science fiction. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Modern interpretation

The first episode, named Nobody, tells a pig monster's story based on the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. It is directed by Yu Shui, who is also head of the animation department at Beihang University.

According to Yu, when people think of the story of Journey to the West, they think of Buddhist monk Xuanzang and his three disciples fighting against the giant monsters in their pilgrimage, while the little monsters they have encountered were often neglected.

"I want to put the perspective on the little monsters who used to have blurry faces and don't even have names in the story," Yu says. Where do they come from? What kind of life do they want to have? What are their woes? Do they have families? With these questions in mind, Yu started to write the story of the pig monster.

The story of Nobody was repeatedly polished by the team, and each detail is well-designed, such as the gourd kettle that the little pig monster carries all the time. In the film, when the pig monster visits his family, his mother explains that she gave him the kettle hoping he would drink more water.

The mother repeatedly urging him to take good care of himself also touches the audience and increases emotional attachment to the pig monster.

Yu likes to tell the stories of small potatoes and he always observes ordinary people's lives around him. "I have a notebook and I'll write down the things I observe in life anytime, anywhere," he says. "I hope Nobody can be watched by the audience repeatedly."

Yu took a year and a half to make the 20-minute episode during which senior artists from the Shanghai Animation Film Studio gave him advice.

After several rounds of discussion and exploration, the final art style was set with a combination of Chinese ink-and-wash painting style and modern cartoon style.

Traditional Chinese painting style is one of the major features in the animation series Yao — Chinese Folktales. [Photo provided to China Daily]

Each figure in the film is also elaborately designed.

The monk and his three disciples' faces are actually not seen in the film, just the outline of the four."Because the story is from the little pig monster's angle, so he cannot see the big heroes, which is the same situation in real life. Also, the film's protagonist is the little pig monster, so their faces may distract the audience," Yu explains.

The dubbing of the monk is done by the same voice actor in the 1986 TV series of Journey to the West, so when his voice comes up, it brings the audience directly to their childhood.

A user named "Ye Lingsheng" on Douban, one of China's most-visited review platforms, comments: "Journey to the West carries all our fantasies about the heroes saving the world. In Nobody, the faces of monk Xuanzang and his three disciples are not shown, which is very thoughtful because in the process of growing up, the heroes are different to everyone- it could be the father who takes us to school or the mother who urges us to drink water eight times a day."

Checking the danmu, or instant comments rolling on screen, has become a habit of Yu. "Unlike screening on TV, when the film is shown online, we can get audience feedback live, especially on scenes the audience reacts to the most," Yu says.

Netizens called the first episode "the workplace survival story of the little pig monster", as the story is told with black humor and aroused strong resonance among young working people.

Yu is touched by the audience's comments and their own creations based on the film — one viewer drew a group photo of the pig monster and his four "colleagues" when they first became the monsters.

Some viewers' understanding of the film is beyond Yu's expectation, yet he is happy. "There is no fixed conclusion in artworks, unlike a mathematical question that has only one answer. So such a pluralistic interpretation is good, and it's also good to have this interaction with the audience."

Traditional Chinese painting style is one of the major features in the animation series Yao — Chinese Folktales. [Photo provided to China Daily]

The animation series Yao — Chinese Folktales includes eight short films and covers a wide range of subjects, from ancient mythological stories to science fiction. [Photo provided to China Daily]