Pan Yue: Diversity and Unity in Xinjiang

On June 12th, the International Forum on the History and Future of Xinjiang, China took place in the renowned ancient Silk Road city of Kashgar. Scholars from various countries specializing in history, archaeology, anthropology and environmental studies gathered together. The excavation and research achievements of Minzu University of China at the site of the Mo’er Buddhist Temple provide another example for the world to understand how civilizations blend and interact.

Picture ▲ Excavation site of the Mo’er Temple ruins: In the distance is a round tower, and in the foreground are the foundations of the Great Buddha Hall and monks' quarters.

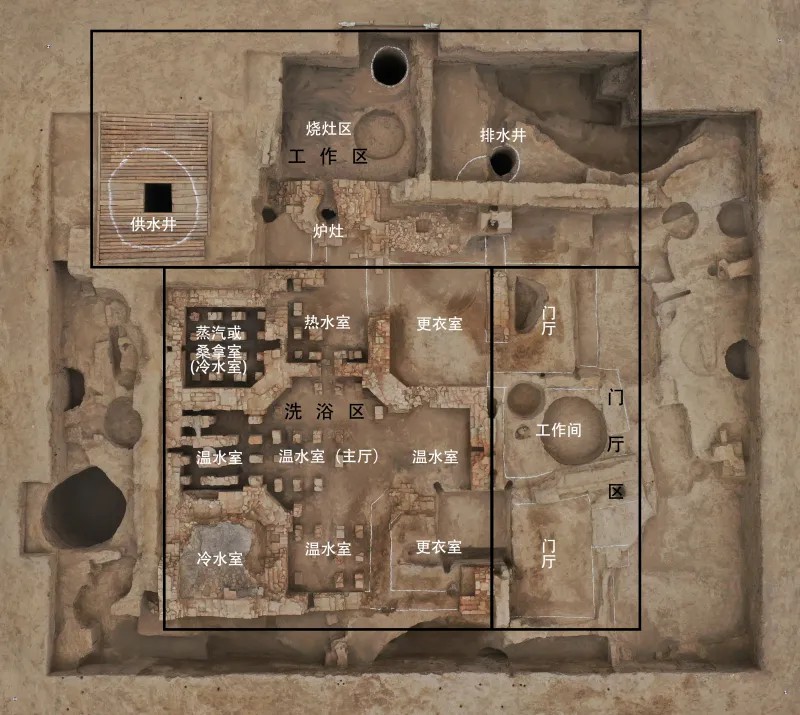

Xinjiang has long been a region of diverse cultures and religions coexisting. Besides numerous Buddhist sites, Tashkurgan County has uncovered a 2500-year-old Zoroastrian fire altar. In the ancient city of Miran, there are 1800-year-old Greek-style "winged angel" Buddhist murals. Turpan unearthed Taoist classics and the Christian Bible from a Christian monastery built 1300 years ago. Manichaean worship scenes from 1000 years ago appear in the murals of the ancient city of Gaochang. In Qitai County, a Tang Dynasty monastery dating back 1200 years depicts the story of "Jesus riding into Jerusalem" in its murals, and a 1000-year-old Roman-style bathhouse has been excavated within the ancient city. These ancient cultures, combined with later Islamic influences, form Xinjiang's diverse religious landscape.

Picture ▲ Floor plan of the large public bathhouse in the Tang Dynasty Dun Ancient City (Image provided by Renmin University of China)

Xinjiang culture is not only diverse but also unified, and this unity is Chinese culture.

Internationally, there's a false narrative that separates Xinjiang culture from Chinese culture, even portraying them as opposing forces. However, abundant archaeological evidence tells us that Xinjiang has been an integral part of the Chinese cultural sphere since ancient times. As early as the Neolithic period, the painted pottery culture originating from the Yellow River basin had spread to both the north and south of the Tianshan Mountains through the Gansu-Qinghai region. Jade, representing state power and ceremonial rites in Chinese culture, has been discovered in cultural sites such as Yangshao, Longshan, Qijia and Yinxu in central China, all of which are associated with Xinjiang's Hetian jade. Even before the Han Dynasty exercised jurisdiction over Xinjiang two thousand years ago, the mythology of Xiwangmu of Kunlun Mountain had already become one of the core myths in the Chinese mythological system. Xinjiang has yielded a large number of Confucian cultural relics from the Han, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties, Tang, Song, and Yuan periods. For instance, remnants of Confucian classics such as the Book of Songs, the Book of Documents, the Spring and Autumn Annals, the Commentary of Zuo, the Analects, the Rites of Zhou, and the Classic of Filial Piety have been unearthed from sites like the Loulan ancient city in southern Xinjiang, the Niya site, and the Astana Cemetery in Turpan. This reflects the historical fact that Chinese culture flourished and bore fruit in Xinjiang. The development of various cultures mentioned earlier here demonstrates the inclusivity of Chinese culture from another perspective. Confucian culture is humanistic, not religious; it lacks exclusivity and can accommodate the coexistence and development of multiple religions. The more inclusive and open it is, the more it is recognized and cherished by all, ensuring the continuous existence of Chinese civilization to this day.

Internationally, there's a narrative that distorts facts, depicting Xinjiang's relationship with Chinese culture as one of "assimilation". This is an ignorant view of Chinese history because the people of the Western Regions have always been co-creators of Chinese culture. For example, the famous Chinese agricultural book Essentials of Agriculture and Sericulture was written by Lu Mingshan, a Uyghur agriculturalist from Gaochang. Many Buddhist scriptures like the Diamond Sutra were translated by the renowned Kuchean monk Kumarajiva, whose coined terms like "compassion", "world", "enlightenment", "ocean of suffering" and "river of love" have become common in modern Chinese. In the Yuan Dynasty, Temür Khan, a Uyghur, served as prime minister and Confucian master under Kublai Khan, promoting Chinese culture. Today, Weigongcun in Beijing, home to many universities, is named after the title "Duke of Wei", bestowed upon Temür Khan. Chinese culture and the Chinese nation have been passed down through generations. The Yuan Dynasty replaced the Song Dynasty but continued to honor Song history, just as the Ming Dynasty honored Yuan history, and the Qing Dynasty honored Ming history. Kangli Naonao, a Mongol from the Western Regions, played a key role in the Yuan Dynasty's restoration of the imperial examination system and in the compilation of Song history. The community of Chinese culture is collectively created by the Chinese nation, including various ethnic groups from the Western Regions.

Picture ▲ Statue of Kumarajiva standing solemnly in front of the Kizil Caves

The foundation of a cultural community lies in the deep integration of economy and society. The geographical conditions of the Pamir Plateau and the Hexi Corridor are crucial factors in the eastward integration of the Western Region's economy. The complementary and symbiotic economic structures between the Western Region and the Central Plains were made possible by the extensive connection between the ancient markets of the Western Region and the Central Plains, enabling the Western Region to serve as a bridge connecting the Eurasian continent. Along the ancient Silk Road jointly opened by the Western Region and the Central Plains, numerous trading cities emerged, among which Kashgar shines brightly. For thousands of years, people of various ethnicities from all directions have migrated, settled, engaged in trade, and intermarried, traversing deserts and sands, resulting in a coexistence and mutual prosperity among the various ethnic groups in Xinjiang. Xinjiang and the Central Plains ultimately belong to the same political community, which is the inevitable outcome of the development of the aforementioned economic, social and cultural community.

Some foreign friends are concerned: if Xinjiang is part of a unified whole, does that mean it lacks "diversity"? According to Western "pluralism", diversity and unity often seem contradictory. However, Chinese philosophy always manages to dialectically unite the diverse and the unified. A significant phenomenon in the history of Chinese philosophical thought, the convergence of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, illustrates this. When Buddhism was first introduced from Xinjiang to the Central Plains, its teachings conflicted with Chinese Confucian and Taoist thought, as it did not emphasize production, respect for ancestors, filial piety, or reverence for rulers. However, Buddhism ultimately absorbed Confucian loyalty and filial piety ethics, reconciled the relationship between karma and filial piety, and adopted Taoist modes of understanding, thereby forming Chinese Buddhism. Confucianism, in turn, absorbed Buddhist metaphysics, giving rise to Chinese Neo-Confucianism. Today, although Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism have not merged into one, they represent philosophical pluralism. Yet, their fusion into a larger spiritual community reflects unity. The melding of diversity into unity, and the reciprocal enrichment of unity by diversity, is exemplified by the Mo'er Temple. In this small site, Indian-style square stupas, Central Asian and local Xinjiang-style courtyard-shaped Buddhist temples, and Han-style Buddhist halls have all been discovered. Spanning 700 years, this reflects the evolution of early Indian Buddhism in the Tarim Basin into distinctive Western Region Buddhism, continuing to spread eastward into the Central Plains. Meanwhile, centuries later, Sinicized Buddhism reciprocally nourished the Western Region, constructing Han-style Buddhist temples in the very places where it initially entered China.

Islam's entry into China followed a similar path. One route was through the maritime Silk Road to Quanzhou, while the other was through the overland Silk Road to Xinjiang, where it clashed with Buddhism, leaving traces in the Buddhist sites of southern Xinjiang. However, the ultimate outcome was that Islam in China began to integrate with Confucianism, Taoism and even Buddhist philosophy during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, giving rise to the concept of "harmony between Islam and Confucianism". Translators of Islamic texts in China at that time emphasized the idea of "reverence for Allah and loyalty to the nation", seeing parallels between Islamic principles of "loyalty, faithfulness, filial piety and friendship" and Confucian ethics. Urumqi has a Shaanxi Great Mosque, built during the Qianlong reign of the Qing Dynasty, reflecting the architectural style of harmony between Islam and Confucianism. This spirit of harmony shares common ground with the rational thinking in the Islamic world, representing an important attempt to reconcile the relationship between state and nation, doctrine and secularism. Malaysia recently held the Islam-Confucianism Leadership Dialogue. Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar stated, "By focusing on the intersection of Islam and Confucianism, we choose to move away from discord." He also mentioned recognizing the teachings of Islam and Confucianism, amongst other things, urging them to strive for a future that is not just advanced in technology but also morally enlightened. The greater comprehension between Islam and Confucianism continues to benefit Xinjiang today.

Picture ▲ Shaanxi Great Mosque located in Urumqi City

Whether it's Buddhism or Islam entering China, both have undergone collisions and assimilation, becoming Sinicized versions of themselves. This collision and assimilation weren't about eliminating each other but about elevating each other, blending to create a more advanced civilization. The story of Xinjiang serves as ample proof that Chinese civilization continually rejuvenates itself through inclusivity.

Most of the experts present here study ancient civilizations, all of which inherently embody natural diversity and seek unity in their own ways. While we may not entirely agree on how to achieve unity, we all sincerely hope to harness the power of unity and cohesion. Through mutual pursuit and learning from each other, we can each achieve our goals.

As a melting pot of diverse civilizations, both in its history and future, Xinjiang will continue to uphold the path of unity in diversity, becoming a safer and more harmonious area. It will play a greater role as a hub, connecting China with Central Asia, West Asia and Europe. It will better support the core area of the Belt and Road Initiative. And it will better protect the excellent cultures of all ethnic groups to enrich and develop the vibrant Chinese civilization. Therefore, Xinjiang is not only China's Xinjiang but also the world's Xinjiang. It is our shared vision to bring the historical, present and future Xinjiang to the world.

The above content is adapted from the speech of Pan Yue, deputy head of the United Front Work Department of the Communist Party of China, minister and Party secretary of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission, at the International Forum on the History and Future of Xinjiang, China. Some parts have been slightly condensed in English compared to the original Chinese text.