Guardians of the Great Wall

Visitors at the ruins of a beacon tower of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) Great Wall in Dunhuang, Gansu province.[Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

Deep in the Gobi Desert in Northwest China's Gansu province, remnants of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) Great Wall stand firm. One layer of fine sand, plus a layer of reeds or rose willow, tier upon tier, has made it through two millennia, from a military installation to a representative living heritage.

Two thousand years of sandstorms has not been long enough to weather it down or diminish the evidence of trade and cultural exchanges between the East and the West, nor has the heavy wind howled enough to prevent people from evoking the glory of the ancient Silk Road.

Rather, the endeavor to keep this part of history alive, in every possible way with manpower and the assistance of technology, will prolong the magnificence that marked ancient people's wisdom, their marching into a more stable, civilized and prosperous society, as well as their adaptation to nature's cruelty in such a barren land.

A family's perseverance

The city of Dunhuang — sitting at the west end of the Hexi Corridor, the main artery of the ancient Silk Road — has a relatively well-preserved section of the Han Dynasty Great Wall.

The Great Wall and the beacon towers in Dunhuang run the length of nearly 200 kilometers through, mainly, no man's land northwest of the city, says Zhang Chunsheng, deputy director of the local cultural relics preservation department.

At the Yumen Pass, or Jade Gate Pass, swallows, with their sharp, forked tails, hover above the roofless ruins of a rectangular fortress. Visitors trudge in the wind, curling themselves up in the inadequate shelter of their clothes.

Looking north, fragmentary wetlands are positioned between a vast land dotted with shrub. In the distance are ruins of the Han Dynasty Great Wall, running east to west, and the natural barrier of the Shule River and Mazong Mountain.

Such a structure was first built in the reign of Emperor Wudi (156-87 BC) of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) to resist the threat from the nomadic Xiongnu tribe, later serving as what today would be a customs office.

Zhang Jianjun and his wife Chen Wanying have been guarding the Hecang Fortress at the Site of Yumen Pass in Dunhuang for 11 years.[Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

During wartime, soldiers applied fire and smoke on beacon towers to pass on military information. During peacetime, the ancient garrison troop engaged in reclamation and grew food.

The Yumen Pass, comprising two fortresses, 20 beacon towers and 18 sections of the Great Wall, is one of the most important passes established by the Han empire at the west end of the Hexi Corridor. More than 2,400 items, including bamboo and wooden slips, silk products, weapons, firewood, farming tools, pottery and lacquerware, among others, have been unearthed there.

In 2014, the Site of Yumen Pass was included on UNESCO's World Heritage List, as part of the "Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor", a transnational property of China, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

A dozen kilometers away from the ruins of Yumen Pass, to an area beyond the reach of mobile phone signals, lizards disguise themselves by taking on the color of the rocks, bodies unmoving, their tape-like tails roll up and unfold nimbly.

Here lie the remains of a military granary — the other fortress of the Site of Yumen Pass, usually called the Hecang Fortress — which also dates back to the Western Han Dynasty. It's located on the bank of a seasonal wetland, several meters above the riverbed, with ventilation to help tackle humidity.

Ranger Chen Wanying's voice breaks through the sound of the visitors' footsteps. She broadcasts the Notice to Visitors from an obscure bungalow nearby and supervises their behavior, in case they cross the fence, accidentally tread on some relics or unknowingly cause damage.

At this time of the year, surface temperatures can reach nearly 60 C.

Zhang Jianjun and his wife Chen Wanying have been guarding the Hecang Fortress at the Site of Yumen Pass in Dunhuang for 11 years.[Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

Chen, 58, and her husband Zhang Jianjun have been living on the sterile land to guard the relics for 11 years. The bungalow, where they work and live, has not been left unmanned for a single day during this period.

They rely on solar power and a wireless network, and there's no running water. The alkaline water from the well nearby is tolerable for cooking, but they need to go elsewhere to fetch drinking water. They usually shop for groceries once a week.

Most of the time the wind emits a ghostlike wail and sounds as if someone, or something, is knocking on the door. On the rare occasions when the wind has exerted itself and needs to recharge its energy, it is replaced by the maddening buzz of mosquitoes.

After all these years, the couple may no longer have the ability to fall asleep in tranquility.

They inspect the relics regularly — their part of the Great Wall extends around 2 kilometers. If there's something wrong, they report to the cultural relics preservation department and let the experts come to inspect and maintain it.

Yet, Zhang Jianjun says, one of the most difficult aspects of their job is to keep wild animals — like oxen, horses, camels and donkeys — away from the wall in the dead of night. Oxen, particularly, like to use the wall to scratch itches brought by insects or parasites, further endangering its integrity. Therefore, the couple have to drive these animals away, a task that often has to be undertaken several times a night.

The situation was worse before. Chen says that, in the past, visitors were allowed to drive their own cars into the scenic area. That is no longer the case. Today, with a fence set up, broadcast and CCTV facilities installed, and shuttle buses available to ferry visitors around, their work of preventing damage has been made easier.

A donkey-driven carriage takes visitors to see the Yangguan Pass, Dunhuang, another important node at the west end of the Hexi Corridor.[Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

The couple's spirit epitomizes the dedication of those who work to preserve the Han Dynasty Great Wall.

Zhang Jianjun was among the 15 individual cultural relics guardians commended by the National Cultural Heritage Administration on June 10, this year's Cultural and Natural Heritage Day, in Chengdu, Southwest China's Sichuan province.

After returning from the trip, he stayed at home for a couple of days. It was the first time since the start of the year that he had gone back home.

Turning 60, it's nearly time for him to retire from a job he's been passionate about. Zhang Jianjun says that he wants to leave the site to his successors intact and pass on the lessons he learned — to do the work well, one needs to be patient, resilient, brave and determined.

Then, they will spend time with their two daughters, and make up for the couple's absence in their youth. The year they took up the job, which offered a more stable income than they'd had as middle-aged farmers, their little daughter was only 13. She was left behind at home and had to take care of herself mostly, as her elder sister was in Beijing working at the time.

Multiple paths, same goal

While staff like Zhang Jianjun and Chen, not well-educated or professionally trained, persevere in preventing improper construction projects and ensuring proper visitor behavior, as well as preventing animals from intruding, the cultural relics preservation department of Dunhuang has been exploring efficient ways to help the Great Wall resist encroachment of nature, and their vision changes accordingly.

Zhang Chunsheng is working on a project to deal with mild, chronic damage brought about by nature.

Plant roots stretch deep into the ground, weakening structures.

Ants and rock bees like to nest on walls, undermining the already fragile structural integrity.

Preservationists used to focus on reinforcing the body of a wall in urgent need of maintenance, but now they also pay detailed attention to such hazards especially at the bottom of the wall, Zhang Chunsheng says.

He adds that, as a local cultural relics preservation unit with limited staff, technical facilities and funding, they need to apply measures with a low cost. These methods should also be replicable, and the standards for operating them should be accessible to grassroots preservationists and volunteers with basic equipment.

The Site of Yumen Pass was included on UNESCO's World Heritage List, as part of the "Silk Roads: The Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor", in 2014. [Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

From his perspective, observation, experimentation and practical experience are highly valued in their work — which involves sites distributed over a wide area — especially in evaluating the effect of preservation measures and finding problems and corresponding solutions.

"Our ultimate goal is to keep the Great Wall healthy and maintain its longevity," he says.

The Great Wall is representative of the genre of earthen sites in China. These earthen relics account for around one-third of the country's 767,000 immovable cultural relics, says Wang Yanwu, director of the relics preservation research department of the Conservation Institute, Dunhuang Academy. The academy is best known for its research and preservation of the Mogao Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and overseeing several other grotto complexes along the Hexi Corridor.

Unlike Zhang Chunsheng's team that focuses mainly on work in situ, the academy's "multi-field coupling laboratory", featuring the preservation of cave temples and earthen heritage sites, reveals the mechanisms behind the "diseases" that can affect relics and develops technical solutions.

This laboratory, the first of its kind in China to be employed in cultural relics preservation, is able to simulate the four seasons, and the erosion by wind, rain and snow that the earthen relics could experience in a natural environment.

It enables experiments on large-sized samples, simulating the actual environment and verifying deterioration of the surface, as well as potential materials and techniques to reinforce the relics.

The laboratory consists of three test chambers, namely summer, winter, wind and rain, which can realize temperatures ranging from-30 C to 60 C and humidity from 10 percent to 90 percent.

The intensity of rain and snowfall, and even the difference in the east-west Great Wall's sun-facing and shaded sides, is under consideration, as the lab analyzes the impact of natural forces.

The largest sample at the lab, for now, is a model wall made from earth taken from near the site of Suoyang City, the ruins of a transportation hub on the ancient Silk Road located around 150 km away from today's Dunhuang city. It's 2.8 meters long, 2 meters tall, 1 meter wide at the bottom and 60 centimeters at the top. It weighs around 15 metric tons.

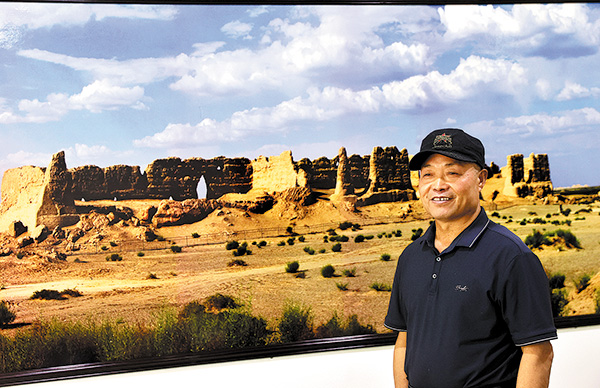

A section of the Han Dynasty Great Wall to the northwest of the Dunhuang city.[Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

Meticulous, repetitive loops, simulating real situations, reproduce the weathering that can be brought about over hundreds of years or more, and make it possible to develop corresponding reinforcement measures. Such processes are closely monitored by sensors and cameras, among other equipment.

Wang says, the idea of building such a laboratory to deal with the surface weathering mechanism of earthen sites and sandstone cave temples, and to develop solutions for it, came from his predecessors, including renowned heritage conservation scholar Li Zuixiong (1941-2019), Wang Xudong, who's now director of the Palace Museum in Beijing, and Guo Qinglin, deputy director of the academy.

They found that effective tests on small samples are often carried out to no avail in the real practice of restoration. It's natural for them to consider the size of the samples.

These scholars began studying the weathering of the earthen relics in the 1990s. Since the laboratory was officially put into use at the end of 2020, the academy has been simulating diverse climate conditions and testing on samples of earth taken from areas nearby key archaeological sites around the country. The samples show similar features with the earth used in the construction of these ancient sites.

In recent decades, the academy's conservation team has been promoting their research at more than 200 locations in 16 provincial-level administrative regions, and is aiming to build a database of the information collected and analyzed. Their work involves research and investigation, design of reinforcement measures, execution and effectiveness evaluation, Wang Yanwu says.

So far, the laboratory has preliminarily completed the exploratory research on the weathering mechanism of the sandstone North Grotto Temple in Qingyang, Gansu province, and the corresponding prevention and control technology. Research on the Mogao Caves will also be carried out in the laboratory.

Wang Yanwu says it has also developed a series of materials and equipment especially for protection of these structures, as well as reinforcement techniques, such as anchoring, grouting and propping, as well as formulating technical standards for their implementation. Together with anti-weathering technology, such as those using chemical or biological methods, or covering the relics with a sacrificial layer or protective shed, they have formed a technical system of earthen site preservation.

International cooperation is emphasized. Wang Yanwu notes that the lab has introduced and further developed the soft capping technique from the School of Geography and the Environment, Oxford University, which is usually applied on limestone and masonry artifacts, and experimented to protect the surface of earthen relics by covering them with a layer of moss or grass, in the hope of reducing drastic changes caused by temperature, humidity or rain.

The lab is also working with academic institutions including Oxford and the Northwest University in China on dealing with weathering. The Getty Conservation Institute in the United States will be involved in the future as well, Wang Yanwu says.